It’s fair to say that with WipEout, Sony got its marketing absolutely spot-on.

In fact, it’s hard to recall another instance in the history of video game marketing when the stars aligned so perfectly. The game’s marriage of cutting-edge visuals, stunning design (courtesy of The Designers Republic) and excellent music delivered the kind of cultural milestone that other publishers dream of; WipEout (and, by extension, PlayStation) became so cool that both were finding their way into the hottest dance clubs of the UK – something that would have been almost unthinkable during the child-focused Mega Drive and SNES era.

However, one of the most notable pieces of marketing relating to the game doesn’t actually feature the game at all – in fact, it doesn’t show any screenshots, any anti-grav ships or even a PS1 control pad. It’s also one of the most infamous pieces of video game promotion the industry has seen – at least in the United Kingdom – and caused a fair amount of outrage and consternation amongst those who simply didn’t understand (or want to accept) that interactive entertainment, like its audience, was growing up.

The WipEout advertisement in question features a man and a woman sitting on a sofa, looking bleary-eyed and covered in blood; both are wearing T-shirts adorned with WipEout-related iconography. Former Psygnosis copywriter Damon Fairclough speaks about this landmark piece of marketing in the recently published WipEout Futurism and explains that he and fellow Psygnosis scribe Huw Thomas “suddenly became these ad production guys who had to sort out all kinds of stuff, like actually casting the ads.”

Those of you who reside in the UK and are over the age of 40 will no doubt recall that this particular ad featured Sara Cox, who, at the time, was an unknown model but was quite literally on the cusp of becoming one of the most famous faces on TV. “We went over to Manchester Model Agency, I think they were called, and saw a load of people,” explains Fairclough, before adding:

Sara Cox was… an absolute nobody at the time. But it was while we were there that the woman in charge called Sara over and said, ‘We’ve got a letter from Channel 4.’ And so Sara opened this thing saying she’d got a gig on The Girlie Show, which was her breakthrough. So she’s absolutely hyper, and everybody else in the room, all these Manchester models, are looking daggers at her, just consumed by jealously. Lots of false smiles. ‘Oh, well done, Sara.’ Sara was also broke at the time; we had to give her a cheque there and then that she could take back to Manchester. She was vaguely interested in this thing being a game, but not much, really.

Cox’s male counterpart in the advert was apparently rushed in at the last second from a London agency, while the photographer was Andy Earl, who had worked with the likes of Pink Floyd, Madonna, Johnny Cash and Prince. “It really felt like going into another world from sitting at my computer all day in Liverpool,” continues Fairclough. “Sara came down on the train, and we set up this little scene with the wallpaper and the sofa.”

It’s ironic that the element of the ad which caused the most fuss – the blood – was supposed to be more subtle:

The nosebleed thing was meant to be the merest hint of blood, but the makeup was by some theatre and film guy who absolutely went to town on it. And already, even while it was happening, there was this slight feeling of, ‘I don’t know how this is going down when we get back to Liverpool.’ But anyway, it happened.

The ad ran for the first time in the UK trade magazine Computer Trade Weekly. “That was where these things tended to get launched every Monday morning,” says Fairclough. “I remember the WipEout ad hitting, which in a trade mag meant this big colour picture. And the shit absolutely hit the fan that morning. In that spirit of breaking new ground and not quite having the right structures in place, it seemed there’d been a not-very-robust sign-off process.”

As is so often the case with the British tabloid media, the headlines were predictably over the top, with The Sun, that long-standing bastion of family-friendly reporting (which, lest we forget, still had a naked woman on page 3 at this point in time), bleating that “an ad for a Sony computer game aimed at kids as young as three has been blasted as glamorising drugs.” Just to make things even rosier for all concerned, the late Tory MP Terry Dicks branded the poster “a complete outrage.”

“A whole load of people from Sony who’d never seen this were suddenly confronted with it in the press and had absolutely no idea what it meant,” laments Fairclough, who is keen to stress that the drugs angle hadn’t crossed his mind when the photos were taken – the nosebleeds were supposed to have been caused by the game’s intense speed, not illegal substances. “The drug inference hadn’t been top of our minds at all, but suddenly, in the cold light of day, it was really fucking obvious. We had to do a bloodless version for the German market, because that’s a legal thing over there, and that one looked even worse!”

Even so, Fairclough feels that the ad’s negative impact has been somewhat overblown as the years have gone by. “It dawned on people pretty quickly that this thing wasn’t doing any harm at all,” he says. “Without social media, we weren’t getting feedback from the punters. The trade [press] were mystified, but then copycat stuff started happening, and things suddenly changed.”

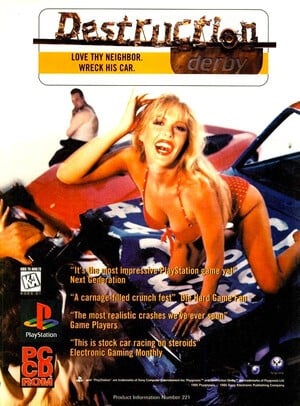

Fairclough says that Psygnosis would continue to use photographic imagery to promote its games until the trend was phased out as rival companies tried to imitate the process without understanding what made it so effective. “It quickly became this thing of companies putting page-three models in their ads, because that’s what we in the game industry were now doing. That was our fault a little bit, but again accidental.” He cites Destruction Derby’s campaign as one which was misinterpreted by other firms. “The Destruction Derby one was a page-three type woman sat on a really bashed-up car, which was meant to be a pisstake of when they’d have a ‘bevvy of beauties’ at car launches.”

We tried to keep the photographic thing going for a little while. There was one ad for 3D Lemmings with all these guys in suits, with green hair, in a London tube station. Krazy Ivan was this big beery Russian guy photographed in the Roman spa in Bath. Discworld was meant to be another one, with all these Discworld characters in a swimming pool for some reason. I presented that to Terry Pratchett’s agent, he was a right one – and he had a face like thunder. ‘On absolutely no account can this go forward.’ Because the Discworld characters can’t appear in our world, apparently. Adidas Power Soccer was supposed to be another one, but then they got Paul Gascoigne involved and the ads became all about him. The whole thing just sort of petered out in the end, with this feeling that everyone was trying to copy it but was doing it all wrong.

WipEout Futurism is available to pre-order from Thames & Hudson. You can read our review here.

Please note that some external links on this page are affiliate links, which means if you click them and make a purchase we may receive a small percentage of the sale. Please read our FTC Disclosure for more information.

Go on.... treat yourself to a new game.

1 Comment

Wow, what a trip down memory lane! The WipEout ad really did stir up some serious controversy back in the day. I remember seeing it and thinking it was edgy and cool, but I can see how it ruffled some feathers. The combination of blood and gaming was definitely a bold move, especially when the gaming scene was still trying to shake off its “kids’ stuff” image.

Sara Cox went from unknown to a household name almost overnight, and that ad was a huge part of it. It’s funny how the intention behind the nosebleed was all about the game’s speed, but it ended up being interpreted as something much darker. Classic miscommunication!

Looking back, it’s wild to see how far marketing has come in gaming. Now, we see all sorts of creative campaigns, but WipEout was really one of the first to push those boundaries. It’s like they were ahead of their time, and while it sparked outrage, it also made people sit up and take notice of video games as a legitimate form of entertainment for adults.