Don’t worry – you’re not suffering from déjà vu. If you feel like you’ve read this before, it’s because we’re republishing some of our favourite features from the past year as part of our Best of 2024 celebrations. If this is new to you, then enjoy reading it for the first time! This piece was originally published on January 13th, 2024.

Whenever Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within is brought up today, it’s usually as a punchline to a joke or as a cautionary tale about a film production spiraling out of control and going way over budget. Yet that doesn’t present a full picture of the complex legacy the film has left behind.

Sure, The Spirits Within was a huge box office bomb and got something of a mixed reception from critics upon its release — with some sources even suggesting its financial failure played a role in the film’s director / Final Fantasy’s original creator Hironobu Sakaguchi leaving Square — but it also laid the blueprint for modern filmmaking with its pioneering use of motion-capture technology to present “photo-realistic” animated humans on screen for the very first time. So, with that in mind, we didn’t just want to treat the film as a punching bag but try and present a more well-rounded retrospective of its creation.

To do this, we pulled from a range of different historical sources and reached out to The Spirits Within’s motion capture director Remington Scott to uncover more about the development, its failure, and its lasting impact on how films are made. Before we get into all that good stuff, though, we should probably go back to the origins of the project to explain how a video game developer and publisher like Square decided to turn its hand to filmmaking in the first place.

Origins & The Gray Test

According to the Making Of feature included on the Blu-Ray release of the film, Sakaguchi first came up with the concept behind Final Fantasy: The Spirits Within in the years following the death of his mother Aki. The event left a tremendous impact on the Japanese creator and led him to begin speculating on what happens to the spirit after death, resulting in the creation of “The Gaia Theory” — a fictional philosophy (inspired by Shinto beliefs and Greek Mythology) that suggests all animate and inanimate objects possess a spiritual essence that returns to the planet at the end of life.

This is an idea that Sakaguchi would first come to explore in 1997’s Final Fantasy VII, represented as an ethereal green-and-white substance called the lifestream that is depicted flowing beneath the surface of the game’s planet, and would later serve as the basis of a science-fiction film script that would become The Spirits Within. While this script would undergo many changes during the production of the film — with Al Reinert and Jeff Vintar eventually rewriting Sakaguchi’s original story — the core idea remained roughly the same throughout, focusing on the journey of a woman called Aki (named after Sakaguchi’s mother) seeking out spirits to free a post-apocalyptic version of earth from a deadly alien race.

Scott explains, “Sakaguchi-san had been creating this series of games, but by the time Final Fantasy VII came out, he wanted to make a film. He came up with the concept that it had to be an international movie. It couldn’t just be a Japanese animated film. He wanted to make something that was more international and he knew he needed to acquire a team globally. Square didn’t think they could do it in Japan. And they were concerned about doing it in Los Angeles because I think they thought they might lose control so they chose Hawaii.”

In 1997, Square set up a new studio based out of one of the most expensive pieces of real estate in Honolulu, Hawaii, with the idea being that this new location would not only develop games but also contain a new entity — Square Pictures — which would be tasked with developing CGI movies. Sakaguchi would be the director of its first movie project, with Motonori Sakakibara (the director of Final Fantasy VII’s cutscenes) coming on board as the co-director of the film. Square also began recruiting a bunch of animators from both the US and Japan, and enlisted the help of the producers Chris Lee and Jun Aida to get the project off the ground.

One of the first things Square’s Research & Development department did at this new location was to put together an early prototype nicknamed “The Gray Project”, to try and pin down exactly what the movie would look like. You can view snippets from this test on the Blu-Ray release of the film, with it containing a scene that didn’t make it into the final film featuring two women (one of whom was called Aki) arguing in an apartment. Internal reactions to this were mostly positive inside the company, but Square wanted to push the realism even further in the finished film and still wasn’t sure of the best way to handle the motion capture. So, at this point, Jun Aida contacted Scott to sit in on a test and offer his advice on how to establish an effective motion capture pipeline.

Scott had cut his teeth working as an interactive director at Acclaim, which was one of the first video game development companies to invest heavily in mo-cap technology, and had also just been the art director at the New York startup Pixel Generation where he had motion captured the Olympic Gold Medallist Kristi Yamaguchi for an interactive ice skating product. He had heard about the Gray Project already from his friends in the film industry, but never expected to become involved with it.

He said, ‘I’m working at a company called Square and we make this video game called Final Fantasy; have you ever heard of it?’ And I was like, ‘I literally just pressed the pause button to pick up the phone.’

He recalls, “I was just at home [in New York] playing Final Fantasy VII and the phone rang and it’s Jun Aida. He introduced himself and he said, ‘I’m working at a company called Square and we make this video game called Final Fantasy; have you ever heard of it?’ And I was like, ‘I literally just pressed the pause button to pick up the phone.’ It was so crazy. They were like, ‘Look, we want to do motion capture. We bought this system and they’ve been playing around with it, but they’re not sure what’s going on. Can you come out and do a test?’ I said, ‘Okay’. I think I had like 48 hours. It was like, ‘Okay, let’s go!”

Scott caught a flight to Hawaii and headed down to the state-owned Hawaii Film Studio, where Square had set up its motion capture stage. This was an old film and TV studio located at the foot of the Diamond Head volcanic crater in Oahu, Honolulu, and had previously been used on shows like Hawaii Five-0 and Magnum P.I., in addition to films like Jurassic Park. During the test, he sat in on the filming of a scene featuring the Deep Eyes, the Elite military force that Aki encounters during her quest, but was shocked at just how slow the process was turning out to be.

“That day, I think they captured like 10 seconds of motion because there was so much discussion,” Scott recalls. “At the end of the day, Jun was like, ‘What are your thoughts?’ And I just rattled them off. I said, ‘You need this, this, this, and this.’ I had all these touchpoints of things that needed to be done and he goes, ‘You’re hired.’ (laughs) I had no idea it was like an interview. I just thought I was coming out to do a consulting thing and it was like, ‘You’re hired’. I didn’t even know what the salary was. They were just like, ‘Whatever! Go home, pack your bags, and be here in two days.'”

Shooting The Film

Scott relocated to Hawaii and initially took the role of a line producer on the film, helping the R&D team to rebuild the mocap system and establish several best practices to help Square reduce the amount of time it would take to animate each scene.

According to Scott, at this point, Square’s motion capture team was not yet solving 3D skeletons using the mocap reference data captured during the shoots but was instead recording point clouds to then hand over to a team of animators to keyframe the puppet inside of in Maya. It was time-consuming, incredibly difficult, and would potentially lead to huge delays when production started. So the solution was for the team to go away and design a new bio-mechanical solver inside of Maya.

“There was a test where 3 characters were walking and the spirits were moving around them, and then a minute or two later one of the characters gets killed. It took someone about a month and a half to animate that. And so we took that motion capture data, applied it [our way] and we put it out, and we had it in like a couple hours. So there was just this pipeline that started to get created. Sakaguchi-san really got a sense of that. So what he said was, ‘You direct it’ and he gave me the role to direct the motion capture.”

How the pipeline worked on the film from start to finish was that Sakaguchi would work with a team of concept artists to create a sketch of all the shots and angles necessary to bring the script to life. He would then arrange them into an animatic storyboard to be passed over to the mocap team, who would then create a rough 3D version of the animatic to allow Sakaguchi to see what it would look like before shooting. Once Sakaguchi had approved this rough 3D version of the scene, Scott would then have permission to go and shoot it, working with the actors to refine and capture their performance. The results of that would then go directly to the animators, who would tweak the facial animations, before moving over to lighting, comp, and eventually final image.

As Scott tells us, the whole film was shot sequentially, from start to finish, which typically isn’t the norm in filmmaking for various reasons such as the practicalities of scheduling with the actors. Here, though, that wasn’t an issue with the motion capture actors turning up for several days to a week every month to film the necessary scenes.

“We’d have these elaborate sets built,” says Scott. “There were things that they were climbing on and interacting with and all of these pieces needed to be accurate to the actual digital versions that they were interacting with in the virtual world because there were issues of scale. If the actor was not the same size as the digital replica, then where they move and how they move is different. So there were a lot of technical challenges to overcome but it was really about figuring out how to make a computer-generated virtual movie. How to do this with motion capture and performers. And there was no template. No one had done this before.”

In total, the development of The Spirits Within lasted for four years, with the cost of inventing a new style of filmmaking and setting up Square’s studio space leading the budget to balloon from a planned $76 million to $137 million.

An Animation World Network article from 2001 estimated that it took 200 people a collective 120 person-years of work to bring the film to the screen, with the same publication also reporting that the finished product contained a whopping 1,327 shots and 141,964 frames of animation (each of which could take anywhere between 15 minutes to 7 hours to render).

“The amazing thing about Sakaguchi-san’s vision is that it is uncompromising,” Scott tells us. “He went all in. He wasn’t concerned about any of those things as far as we can tell. He was like, ‘We’re going to create a new piece of cinema’ and we followed him and he led us into new territory. I don’t think he’s been recognized for that as much as he should be. His vision in cinema is yet to be appropriately recognized.”

Bombing At The Box Office

Final Fantasy Spirits Within premiered at the Mann Bruins Theater in Los Angeles, California on July 2nd, 2001, and was released in theatres in the US later that month (July 11th). Square Pictures had especially high hopes for the film, being proud of what it had been able to put together, but on its opening weekend, the film earned just $11.4 million — far below what it had initially expected.

Reviews for the film were mixed. Roger Ebert was one of the critics who championed the movie, praising it for its astonishing use of technology:

“Is there a future for this kind of expensive filmmaking ($140 million, I’ve heard)? I hope so, because I want to see more movies like this, and see how much further they can push the technology. Maybe someday I’ll actually be fooled by a computer-generated actor (but I doubt it). The point anyway is not to replace actors and the real world, but to transcend them–to penetrate into a new creative space based primarily on images and ideas.”

Meanwhile, the BBC’s film journalist Danny Graydon struggled to look past the shortcomings of its story, lamenting that its four-year journey to the screen didn’t result in a more cohesive plot:

“With a plot that freely plunders the likes of “Aliens” and “Starship Troopers”, the visual grandeur cannot hide clichéd dialogue, thin characters, and a frustrating lack of development. Where most blockbusters would go for the big-bang ending, “Final Fantasy” is content to indulge its spiritualist angle, resulting in a damp ‘healing power of love’ conclusion, replete with pointless sacrifice.”

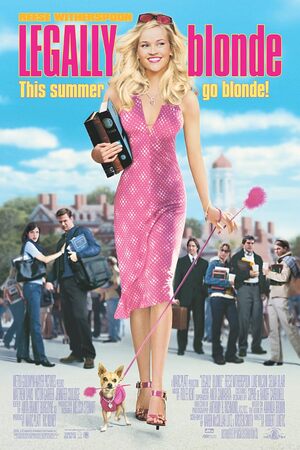

Scott recalls when he first started to notice something was dreadfully wrong: “I was on the beach having a wonderful Sunday when my friend called me up and said, ‘Congratulations! You guys came in fourth at the box office.’ I was like, ‘What?’ He was like, ‘Yeah, Cats & Dogs, The Score, and Legally Blonde beat you guys!’ I thought, ‘Wow, that’s not that good.’ So I knew that Sunday on the opening weekend, but I wasn’t paying any attention to it. I was like, ‘Let’s go have a nice relaxing day.’ And then that night, I was like, ‘This is not good, because this movie needed to be number 1 at the box office.’”

Scott has many theories about why the film did so poorly with audiences. He, of course, accepts there were probably faults with the content of the film itself, acknowledging Sakaguchi’s decision to set the game in a science-fiction setting was a gamble considering fan expectations, but also suggested that the marketing also didn’t do the film any favours.

As he recalls, Sony Corporate had enthusiastically agreed to distribute the film due to the company’s great pre-existing relationship with Square but during production, its marketing shifted over to the Sony subsidiary Columbia Pictures which struggled to know what to make of a film that was evidently the first of its kind.

“They were like, ‘Who’s starring in this movie?’” says Scott. “‘Well, no one! It’s a bunch of computer-generated humans.’ ‘How are we going to market this movie then? How about we put the marketing on the Cartoon Network channel.’ Because it was first, you had a group of people behind the movie studio who didn’t know how to handle that. So there was not an awareness when the movie came out of what this was. There were some vague posters of faces, of computer-generated guys that you’ve never seen before, but you don’t know who they are. They can’t open a movie. And it was a marketing campaign that completely missed its target audience. So that was a pretty big factor.”

Besides the lousy promotional campaign, Scott also brings up another potential issue. In the run-up to the movie, some high-profile actors expressed concerns in interviews about the film’s use of virtual actors, claiming that they weren’t enthused about the idea that their performances could be tampered with after the fact or that someone might make unwanted use of their digital self. For instance, in a New York Times article in July 2001, Tom Hanks, the star of Toy Story (and later Polar Express) stated, ”I am very troubled by it. But it’s coming down, man. It’s going to happen. And I’m not sure what actors can do about it.”

“He verbally spoke against this movie,” remembers Scott. “There were records where he was saying, ‘This scares me.’ I think there were other filmmakers too like Steven Spielberg that got vocal as well during this. But if you look behind the scenes, within a few years of Final Fantasy coming out, Tom Hanks was starring in Polar Express as five digital characters and they were trying to say, ‘We’re making the first performance capture movie ever.’”

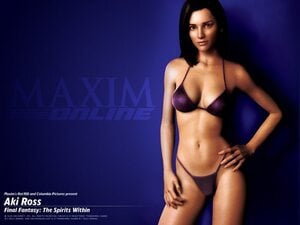

Following the release of The Spirits Within, Square was planning to create a series of feature films that included its lead star and “virtual actress” Aki Ross playing a bunch of other roles but plans for this were quickly scrapped after the film bombed with audiences.

Square Pictures instead found itself working on The Animatrix short film “Final Flight of the Osiris” (which was eventually released in 2003) in addition to two other film ideas.

“What Square was trying to do was try to secure another deal,” says Scott. “Moto[nori Sakakibara] was developing his own unique thing, but it was a completely cartoon-type of thing. It wasn’t within the aesthetic that Sakaguchi-san had set up. Then there was another group, which I was involved with, where there were discussions of doing a Gerry Anderson UFO movie. We thought we were going to kill it. Like this was going to be amazing. But then, unfortunately, the studio closed down.”

Square Pictures officially announced it was shutting its doors in October 2001, citing “extraordinary losses” that were believed to be as high as 3.16 billion yen, or 115 million US dollars.

In the aftermath, recruiters from places like ILM and Weta flocked to Hawaii to pick up some of the best talent from the ailing studio, with Scott personally going on to assist on The Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, helping the director Peter Jackson to realize the motion capture character Gollum.

He explains, “I got a call and it was an associate at Weta who said, ‘Peter Jackson wants to talk to you. Are you available?’ So Peter came on, we spoke, and he was like, ‘We want to do [motion capture] performance. We want to see if there’s a pipeline to do that. Can you come down and check it out?’ So I said, ‘Sure, I’d love to.’”

As for The Spirit Within’s director Sakaguchi, he eventually left Square altogether in 2003, deciding to start his own video game company Mistwalker. Its latest release is the 2021 RPG Fantasian, which was published on iOS devices.

Go on.... treat yourself to a new game.